Home advantage and the Indian XI’s scorching performances in the last month imply that we are nearing the end of the season, but concerns persist.

The thunderous sound of fireworks being exploded outside interrupted Team India skipper Rohit Sharma’s opening press conference following India’s crushing triumph in the Asia Cup final. He stopped, allowing the din to wind down, and then exclaimed, almost reflexively, “World Cup jeetne ke baad phodo, yaar (Burst the crackers after we win the World Cup, guys)!” While Rohit’s remark was intended in fun, it captures the spirit of a cricket-crazed country that has been without a global trophy since 2011, when M.S. Dhoni led the Indian team to triumph.

There might be no better moment or venue to put an end to that agony than the ODI (one-day international) World Cup in 2023. If there was a 28-year gap between when Dhoni’s Daredevils lifted the cup and when Kapil’s Devils won it for the first time in 1983, the hope is that ‘Rohit’s Roarers’ will break the stalemate this time. The ODI World Cup is regarded as the G20 of cricket, the pinnacle of the white ball limited overs format. The World Cup has developed as cricket’s flagship event since the advent of one-dayers in 1975, earning worldwide acclaim as well as the sport’s largest prize money—the 2023 edition has a total reward of $10 million, or Rs 83.3 crore.

The previous edition had a global cumulative live viewership of 1.6 billion people; expect a 40% increase this time as the circus moves across 10 venues, encompassing 48 games over 46 days.

THE STRENGTHS OF INDIA

So, can the Indian team be able to pull it off? Since their win in 2011, they have been found wanting on the largest stage, particularly at critical junctures (see box Dry as Dust). The word was out: India can be beaten, and in a variety of ways. The Men in Blue arrived in Sri Lanka for the Asia Cup last month with a lot of questions: the openers had been struggling; Virat Kohli had gone through an extended dry spell in ODIs; K.L. Rahul and Shreyas Iyer’s match fitness was in doubt; all-rounder Hardik Pandya hadn’t been in action as a bowler for long;

Bowlers Shardul Thakur and Axar Patel appeared to be in the team not because of their performances, but because there was a desperate need for allrounders to balance the playing XI; and ace speedster Jasprit Bumrah was returning from a long-term injury with no evidence that he had regained the form or strength to bowl the 10-over quota. Four weeks later, all misgivings have been dispelled, with the Indian XI dominating the continental title and then decimating a full-strength Australian team in a short pre-Cup ODI series.

India had to wait 28 years after Kapil’s Devils won the World Cup for the first time in 1983. Will this be Rohit Sharma’s final performance after 2011? The picture of M.S. Dhoni’s six to win the game in the 2011 final is imprinted in the minds of every Indian cricket fan.

The alert had been broadcast to the rest of the cricketing globe. Shubman Gill, India’s highest ODI run-scorer this calendar year, is one of the most promising young batters in the world. Aside from his spectacular stroke-play, the 24-year-old’s ability to convert solid starts into significant knocks is clear confirmation that he has a mature head for his age. Captain Rohit Sharma, fresh off reaching Mount 10K in one-day cricket, appears to have finally struck the balance he’d been looking for between attack and defense—an strategy that saw him end with the best strike rate among the Asia Cup’s top six run-getters.

If anyone had any doubts about Virat, he delivered a timely reminder of his ODI brilliance by blasting a match-winning century in a crucial game against Pakistan. The fact that he is currently only two centuries short of Sachin Tendulkar’s all-time ODI record of 49 tons should be enough to fire him up for the World Cup. K.L. Rahul has risen from the ashes like the traditional phoenix. After recovering from a serious back ailment, the substitute wicketkeeper/middle-order hitter has returned his place in India’s starting XI. His outstanding batting average of 93 since his return, along with the fact that he has been keeping wickets in all matches—embellished with some stunning catches and exhibiting no indications of injury—has aided India in more ways than one.

Hardik Pandya, the batter, was never a concern. Hardik Pandya, the T20 bowler, was also a valuable asset. The verdict on Hardik Pandya, the ODI bowler, was still out. The Asia Cup, on the other hand, offered an unequivocal verdict: the tremendous pace and control with which the vice-captain bowled belonged to a full-time ODI bowler, not the sixth bowling option he was frequently regarded as.

Indeed, India’s bowling unit has become the talk of the town. Bumrah is bowling like he’s never been out of international cricket, dismissing top-order hitters with a combination of sheer pace and clever settings, exactly as he did before his 11-month injury layoff. Kuldeep Yadav, the Asia Cup’s man-of-the-tournament, has the entire cricket world scratching their brains, trying to figure out his incorrect ‘un. And the ever-exuberant Mohammed Siraj has had helpless rival batters floundering around with his wobbled seam and extra bounce (his six-fer in the Asia Cup final was proof of that).

From not knowing what their ideal XI was just about a month ago, to becoming the ‘idol XI’ of ODI cricket has marked quite a dramatic turnaround for this Indian team. It’s this assortment of match-winners that has allowed India to win handsomely in recent one-dayers, including the three-match series against Australia that saw a rearguard fightback by the middle-order pair of K.L. Rahul and Surya Kumar Yadav to seal the first ODI and a Gill-Iyer blitzkrieg that took India to a record total of 399 in the second. Quite clearly, this multi-pronged attack could be the X factor if India is to land the biggest prize in cricket.

CHINKS IN THE ARMOUR

But work through the sturdy Indian exterior and examine the finer details and some cracks begin to appear in the arsenal. The lack of all-rounders, for one. Much like today’s corporate workplace where multi-tasking is the buzzword, multi-dimensional players have become a necessity in cricket; more so in one-day cricket where the premium is on bowlers contributing with the bat and vice versa. This was also India’s secret sauce during the 2011 World Cup as the likes of Yuvraj Singh, Suresh Raina and Yusuf Pathan—all proper batters—chipped in with vital breakthroughs with the ball. But that’s a luxury this current Indian team cannot afford, with none of their top-order batters bowling at the international level consistently.

The new power-play rules—five fielders inside the 30-yard circle between overs 11 and 40—are to blame. It was introduced in 2015 to rid the format of the ‘boring’ middle phase, but it gives the bowlers no break. When combined with another rule change that requires two new balls from both ends (as opposed to only one ball for the full 50 overs previously), the ODI format appears to have changed dramatically since 2011. A firm, relatively new ball that comes on to the bat is significantly more favorable to stroke play than a worn-out, 40- or 50-overs-old ball that comes off the pitch slowly. As a result of the rules, teams have adopted the reckless batting approach of T20 cricket in ODIs as well, as evidenced by the results.

as evidenced by the rising team totals in the 50-over format. Since the 2011 World Cup, 15 of the 24 occasions when a 400-plus score has been scored in ODI cricket have occurred.

Whatever the causes for the imbalance between bat and ball, the inflexibility caused by a dearth of genuine all-rounders significantly compromises the Indian XI. In a competition when most top contenders bat as deep as No. 10, India may list hitters up to No. 8 by relying on all-rounders like Shardul, Axar, and Ashwin. Then there’s the ‘fear-of-failure’ charge, which the team faces on a regular basis. Its origins may be traced back to India’s seeming failure to deliver on the big day, particularly in the knockout stages of world cups. On D-days, truly world-class teams are known to up their game a notch or two by playing boldly. India, on the other side, has been discovered to be playing percentage (read: safe) cricket.

Cricket was played at the same time. Is it the weight of 1.44 billion Indians’ expectations that holds them down? “Indians play stats-driven cricket… they are overly concerned with their stats.” “They are so afraid to take risks because of what might be said or printed,” remarked former New Zealand batsman Simon Doull during a recent Sky Sports show. Will this ‘enfeeblement’ be exacerbated by the fact that India is the hosts, which implies pressure? And even more pressure.

THE HOME BENEFIT

In contrast, the ‘home advantage’ provides India with its greatest potential. The fact that the hosts have won the one-day title in the last three editions tells a significant tale. Home teams obviously have an advantage due to their familiarity with the conditions. And nowhere does this better than India, in India. Between the last World Cup in 2019 and today, India’s win-loss ratio at home is a whopping 3.33 (winning 20 games and losing only six). Since 2019, no side has an advantage in head-to-head comparisons in ODIs played in India. And, while the idea that the Indian Premier League (IPL) has helped foreign players adjust to Indian conditions is valid, the statistics show otherwise.

that India’s home advantage remains an overpowering proposition for most opponents.

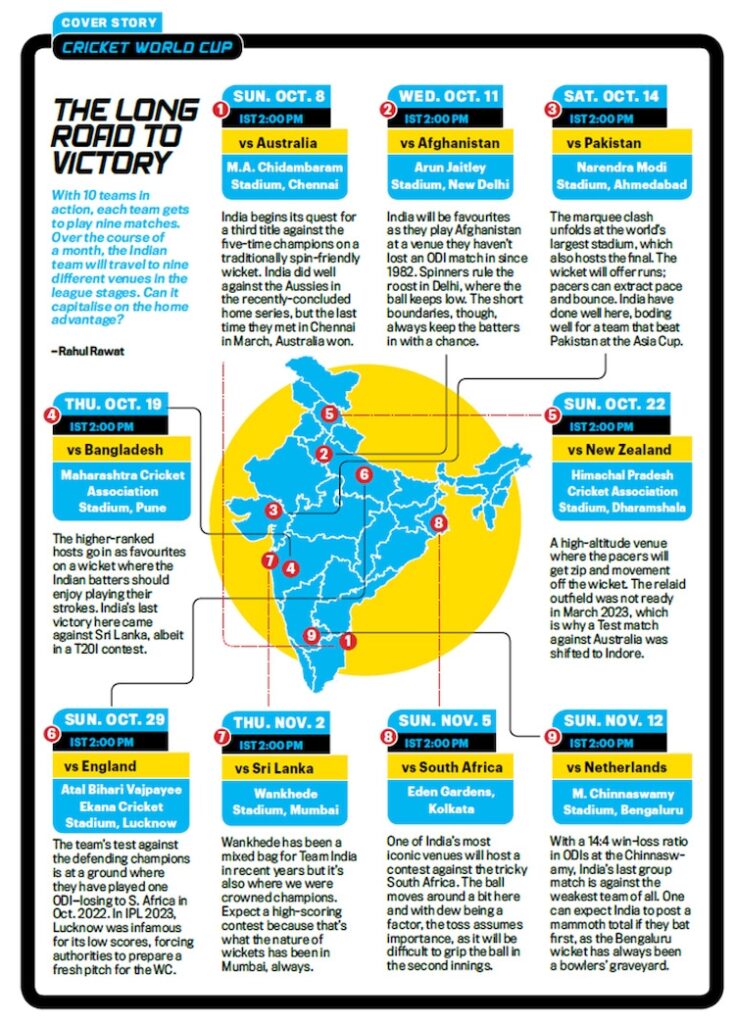

Former Indian team member Harbhajan Singh elaborates on India’s technical advantage when playing at home. “Indian batters are better at piercing gaps than other teams.” “It’s primarily because they use pace and bounce better at home,” explains the 2011 World Cup winner. “While other teams, such as Australia and England, must take risks in search of boundaries in India, our batters, who are familiar with the ground conditions, can increase the scoring rate without taking any.” As a result, we have more boundary-hitters on our team than any other.” During the group stages, the Indian caravan will visit nine different locations (see The Long Road to Victory). And, as the current ODI world No. 1, India will start as favorites in every game.1 ranking and their excellent form over the last month

The venues will also be beneficial. England and Australia will meet India on spin-friendly grounds in Lucknow and Chennai, respectively. With its pace-bowling power and slightly inexperienced batting, Pakistan will want a low-scoring game to give itself the best opportunity of defeating India. However, expect Ahmedabad, the venue for the India-Pakistan match, to provide a track with plenty of runs, hence favoring India’s batting strength. Only New Zealand and South Africa, in Dharamshala and Eden Gardens, respectively, have the potential to offset India’s home edge, as both opponents will enjoy the seam-friendly conditions on offer at these venues. Even so, with India’s pace-bowling arsenal of Bumrah, Shami, Siraj, and Pandya,The Indians would be ahead if they were firing on all cylinders.

However, India would not want to rely solely on domestic conditions. Coach Rahul Dravid, a man who always trusted his methods and process as a player, will have developed a 360-degree roadmap, with data-driven strategies and match-ups playing an important role in the campaign. Dravid has a lot on the line as well. The Board of Control for Cricket in India (BCCI) brought in the seventh-highest run-scorer in international cricket history with one goal in mind: to win a world championship. Dravid’s two years as captain have been marked by departures from the 2022 T20 World Cup semi-finals and a loss in the 2023 World Test Championship (WTC) final. As a result of this

This could be the Wall’s final act. “I believe it is abundantly clear that nothing less than a World Cup victory will suffice for the Indian public.” “The legacy of Dravid and even Rohit Sharma as coach and captain will be determined by where India finishes this World Cup,” Sunil Gavaskar, batting icon and 1983 World Cup winner, told India Today.

RISKS AHEAD

‘Never write off New Zealand in an ICC event,’ ‘Pakistan is always dangerous,’ and ‘Underestimate South Africa at your peril,’ we’ve all heard. Aside from these hurdles, the two biggest threats to India will be Australia and England. England’s approach to redball cricket has garnered a lot of attention. It’s essentially ODI-style batting where batsmen maintain a healthy strike rate by going after bowlers and forcing captains to spread the field (picture many Virender Sehwags in a single batting lineup). It’s dubbed ‘Bazball,’ after their Test coach Brendon McCullum. However, it is England’s approach to whiteball cricket that is revolutionizing the game. The outcomes give witness to this: The ODI is being played in England.T20 world champions, however they haven’t competed in a WTC final and last took home the Ashes in 2015.

The Three Lions’ success has been attributed to their fearless approach; no matter the match circumstances or the number of wickets lost, English batters never seem to rein in their aggressive tendencies. Also true of Australia. Of course, the reason these two teams can bat as deep as they do is their extensive pool of talented players. As a result, they have the luxury of being aggressive throughout their whole hitting innings. In contrast, a side like India is scrambling to find a spinbowling all-rounder just days before the Cup. Axar Patel’s injury has forced the team to revert to 37-year-old Ashwin, who had not played an ODI since 20 months prior to his recall for the home series against Australia.

The differences are really noticeable. There are many variables outside of cricket logic that must be in place for India to replicate its triumphs from 1983 and 2011. In October and November, the late-evening dew makes winning the toss essential. Add the element of chance to that as well—the occasional runout, dropped catch, or rain delays. No squad can succeed if they don’t have the luck of the green. The Cricket World Cup is one of the finest sporting events ever because of these magnificent uncertainties.